The theories that have developed in the field of psychological types after Jung can be roughly divided in the following categories: the relationship between the functions, reformulations of Jung's typology, and various refinements concerning bi-polarity, types and archetypes, and the inferior function.

The Relationship Between the Functions

This first development attempts to fill the gaps left by the very brief descriptions given in Psychological Types about the auxiliary functions. Wayne Detloff, for example, describes the relationship between the superior and auxiliary function:

"...the extravert's principle function is extraverted, but his auxiliary function is likely to have a cast of the introverted side. Thus, the extravert's auxiliary function helps him to relate to his inner world but, since it is his second best function, one can anticipate some difficulty. For the introvert, the principle function is introverted, but his outer adaptation is often complicated because his auxiliary function (second best) is more likely to appear in relation to the external world. Thus, outer adaptation more often manifests the introvert's difficulty." ("Psychological Types: Fifty Years After", p. 70)

This idea had appeared early in the development of the Myers-Briggs test, in fact, in the original formulations of Katharine Briggs after she had read Psychological Types. Isabel Briggs-Myers felt that the practical utility of psychological types was unexplored because Jung failed to bring out this point with sufficient clarity:

"In view of Jung's deep appreciation of the introverts' value, it is ironical that he lets his passion for the abstract betray him into concentrating on cases of "pure" introversion. He not only describes people with no extraversion at all, but seems to present them as typical of introverts in general. By failing to convey that introverts with a good auxiliary are effective and play an indispensable part in the world, he opens the door for a general misunderstanding of his theory." (Gifts Differing, p. 18)

She attempted to remedy this reading of Jung in itself highly debatable, for Jung always describes the introversion and extraversion of each type - by her judgment and perception scale. She explains this use of the auxiliary as follows:

"The basic principle that the auxiliary provides needed extraversion for the introverts and needed introversion for the extraverts is vitally important. The extraverts' auxiliary gives them access to their own inner life and to the world of ideas; the introverts' auxiliary gives them a means to adapt to the world of action and to deal with it effectively." (p. 19)

"Good type development thus demands that the auxiliary supplement the dominant process in two respects. It must supply a useful degree of balance not only between perception and judgment but also between extraversion and introversion.. To live happily and effectively in both worlds, people need a balancing auxiliary that will make it possible to adapt in both directions - to the world around them and to their inner selves. (p. 21)

This idea has been amplified and developed by her close collaborator Mary McCaulley:

"When both the dominant and the auxiliary functions have become differentiated, the individual achieves a balance. He thereby avoids aimless drifting, which can come from total reliance on a dominant perceptive process, or a rigid reliance on form rather than content, which can come from total reliance on a dominant judgment process. In Jung's view, type development is a lifelong process. In midlife some rare individuals can develop to the point where they transcend their preferences and move easily from one function to another as the occasion demands. The MBTI, however, is concerned primarily with normal, rather than exceptional, personality development. In her characterizations of the sixteen types... Myers assumes that both dominant and auxiliary functions are well developed, but she also notes the typical problems to be expected if the auxiliary function is not developed." (1981, p. 301)

Despite the fact that Myers takes Jung to task for neglecting this principle, she feels he alludes to it cryptically in the following passages:

"The relatively unconscious functions of feeling, intuition and sensation, which counterbalance introverted thinking, are inferior in quality and have a primitive, extraverted character." (Psychological Types, 1923, p. 489) "When the mechanism of extraversion predominates... the most highly differentiated function has a constantly extraverted application, while the inferior functions are found in the service of introversion." (1923, p. 426) "For all the types appearing in practice, the principle holds good that besides the conscious main function there is also a relatively unconscious, auxiliary function which is in every respect different from the nature of the main function." (1923, p. 515)

These first two quotes appear to say nothing more than what Jung is continually saying throughout his Chapter X, that is, the conscious superior function is balanced by the other unconscious functions which differ in attitude from it. He realizes he is oversimplifying by not talking about the development of the auxiliary functions, but for clarity's sake he groups them in attitude with the inferior function.

The third passage appears to make a stronger case, but it has to be read in context. Then we see it comes in the middle of a discussion about the nature of the auxiliary function as a servant of the superior function:

"Hence the auxiliary function is possible and useful only in so far as it serves the dominant function, without making any claim to the autonomy of its own principle.

For all the types met with in practice, the rule holds good that besides the conscious, primary function there is a relatively unconscious, auxiliary function which is in every respect different from the nature of the primary function. The resulting combinations present the familiar picture of, for instance, practical thinking allied with sensation, speculative thinking forging ahead with intuition, ..." (Volume 6, p. 406)

Its whole tenor is not to give the auxiliary function a role separate from the superior, but precisely the opposite. If we understand "different in every respect" as a complete sort of opposition rather than a state of undevelopment, how can it serve and serve intimately the superior function, as in the case of practical thinking allied with sensation, etc.?

Furthermore, emphasis on the opposition between the superior and auxiliary function can easily be misconstrued as if their balancing created an individuation that is suitable for normal people while there is another kind of individuation which deals with the inferior function, and the arrival at the self which is reserved to exceptional cases.

Nor is it clear that opposition between the superior and auxiliary functions should be elevated into a universal principle. For example, we had contact for several years under varying circumstances with a man whom we concluded was an introverted sensation thinking type. In the course of a typological interview he also typed himself in this way and was happy with the fit of it. The administration of the MBTI, Form F, showed the predominance of introversion, sensation and thinking, and so was consistent with the other evaluations, but the judgment-perception preference would have made him an introverted thinking sensation type. This was not the case, and the same problem has arisen in other situations. Mary Ann Mattoon's opinion is:

"That they are of the same attitude seemed to be Jung's assumption, on the basis, perhaps, that the more conscious attitude is linked with the two more conscious functions, and the more unconscious attitude is linked with the more unconscious functions. My clinical experience generally supports this hypothesis." (Jungian Psychology in Perspective, p. 67)

On the other hand, Briggs and Myers noted the support for this principle in van der Hoop, and we have seen Detloff's comments, and more recently, Alex Quenk develops quite the same position in his Psychological Types and Psychotherapy. (p. 12-13) This kind of experience cannot be lightly discounted. Is it possible to find a way out of this dilemma? John Beebe in "Psychological Types in Transference, Countertransference and the Therapeutic Interaction" provides 4 direction in which to look for a solution. He accepts the opposition between the superior and auxiliary function, and extends it through the whole personality. An extraverted intuition thinking type would not only have introverted thinking but extraverted feeling, as well as introverted sensation: "My model extends the bipolar assumption to its logical conclusion, namely, that not only the functions but their attitudes as well are opposites along a given axis." (P. 153)

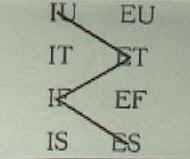

| By extending the notion of bipolarity, Beebe creates type profiles useful in exploring different kinds of transference and countertransference, and he avoids the impression of limiting the perspective of typology to the first two functions. He opens the door to a wider view of the dynamic nature of typology. The type profile of the introverted intuition thinking type would, according to Beebe, look like this: |

|

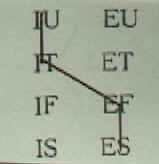

| But it is clear that this profile represents only half of the type. What is to prevent type development taking different pathways, depending on varying circumstances and different natural inclinations? Another schema of development would look like this: |

|

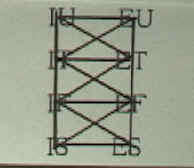

| And a complete one would look like this: |

|

This last model gives us a sense of the actual complexity that we already saw in type diagnosis, and which extends to the question of type development. It alerts us to potential patterns of psychic energy within the overall pattern formed by the superior and inferior functions, and provides a framework for talking about how we deal with the shadow's side of our superior function, that is, the same function with an opposite attitude, and how all these typological fragments can be related to the one personality and to the self. Here we might keep in mind the suggestive remark of Detloff: "The Self then might be conceived as having the potential for all the types." ("Psychological Types: Fifty Years After", p. 70)

Types and Archetypes

Scattered here and there in the literature of Jungian typology are interesting remarks about the relationship between types and archetypes. Groesbeck, commenting on a passage in Jung, states, "...in our shadow, anima, persona and ego figures we may find clues to our typological condition." (p. 32) And Beebe writes:

"...One has to recognize that characteristic archetypal personages carry the various functions according to their degree of differentiation within a given individual's type profile." (p. 157)

And he goes on to illustrate this principle by interpreting dreams typologically, a process which he finds can be aided even by the colors which appear in different dreams with blue representing thinking, red feeling, yellow intuition and green and sometimes brown sensation.

For von Franz if someone has only developed the superior function, then the shadow, animus and anima will appear in the auxiliaries as well as the inferior function. (The Inferior Function, p. 54) But she seems to imply that once the auxiliaries are developed, then these archetypal realities are mirrored in the inferior function. "In dreams, the inferior function relates to the shadow, the anima or animus, or the self, and it gives them a certain characteristic quality. For instance, the shadow in an intuitive type will often be personified by a sensation type... Then when one has become somewhat conscious of the shadow, the inferior function will give the animus or anima figure a special quality." (p. 54-5) The same will happen with the self. Here we have a glimpse of the dynamic development of the psyche seen typologically, and perhaps it throws light on the question of the attitude of the auxiliary function. As we develop, we push back the frontiers of our conscious personality, and the archetypes we relate to and the psychological functions through which they approach us can change.

These interesting remarks could be the beginning of a careful evaluation of how dreams can be interpreted typologically and how typological development is reflected in them. If we have thinking or feeling as our third function and we have developed our auxiliary function, does this mean that the thinking and feeling will carry the anima and animus? Is there a special affinity between thinking and feeling and the anima and animus? Does the third function feeler relate to the anima more easily than the fourth function feeler? If a third function feeler relates to his feelings, does he thereby deal with the anima and constellate another archetype, or does the anima in some way shift and show a face of itself that is connected with the inferior function? It is possible to read Hillman's remarks about feeling and' the anima in this connection (The Feeling Function, p. 121), or different remarks of Jung, for example, the vivid statement he made in a letter to Count Keyserling, who on one of his travels had activated his inferior function loaded with the contents of the collective unconscious: "Simultaneously the anima emerges in exemplary fashion from the primeval slime laden with all the pulpy and monstrous appendages of the deep!" (Letters, Vol. 1, p. 84)

Reformulations of Jung's Typology

Mann, Siegler and Osmond in "The Many Worlds of Time" provide an excellent example of how the boundaries of psychological types can be extended. Invoking von Uexkull's A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men, which describes various umwelts or experiential worlds, they tried to understand what these experiential worlds would be in relationship to time and type. They suggest that the sensation type is present-oriented, the feeling type past-oriented, the intuitive type future-oriented and the thinking type linear, that is, someone who links past, present and future. And they illustrate these different perceptual worlds by abundant examples.

In "Typology Revisited: A New Perspective" Osmond, Siegler and Smoke attempt a more radical restructuring of typology, impelled by our old friend, the diagnostic problem:

"While Jung's typology has proved fruitful as a therapeutic instrument, it has been an unqualified failure as a reliable method of establishing people's types. There has been no growing file of agreed-upon examples of different types, no growing body of knowledge about the characteristics of each type." (p. 207)

In order to resolve this problem they propose a reorganization of the functions in which they will be linked in four pairs:

| Thinking-sensation Sensation-thinking |

Feeling-intuitive Intuitive-feeling |

| Intuitive-thinking Thinking-intuitive |

Feeling-sensation Sensation-feeling |

They call these pairs the "structural", "oceanic", "ethereal" and "experial", and then they go on to give descriptions of these four basic forms by which a person experiences the world. But while reading these interesting descriptions filled with typological analyses of famous people, the reader suddenly comes to himself and asks, "What happened to introversion and extraversion?" And the authors have given their answer right at the beginning of the exposition:

"We shall leave out the two attitudes, introversion and extraversion, which are independent variables of the functions." (p. 207)

Unfortunately, the functions are not really conceivable in this sort of vacuum. They are precisely Jung's attempts to more carefully delineate introversion and extraversion, and the four functions, themselves, appear very differently, whether they are introverted or extraverted. As Detloff puts it:

"It is very important to realize that the two attitudes (extraversion and introversion) so modify the appearance of each of the four functions that the terms are almost misleading. One can sometimes wish that a completely different term were used for a function when it is introverted from when it is extraverted, but, if one knows that the appearance of a given function is modified by introversion-extraversion and associated functions, changing of terms is unnecessary." ("Psychological Types: Fifty Years After", p. 70)

There is a real difference between sensing-thinking and thinking-sensing, as can be seen in an extreme way between an introverted sensation-thinking type and an extraverted thinking-sensing type. And when we make abstraction of introversion and extraversion, they have an uncanny way of creeping back into our descriptions. So our authors make statements like: "Oceanics learn to handle impersonal problems by subjectifying them, as Structurals learn to handle personal problems by objectifying them." (p. 211) Or, "What is real to the Ethereal is the psyche, experienced as synonymous with the mind, and the limitless possibilities offered by the mind." (p. 213)

The use of these compound categories was taken up by Michael Malone in Psychetypes: A New Way of Exploring Personality. But his efforts in this direction did not meet with the approval of its originators.

In "Towards a Reformulation of the Typology of Functions" R. Metzner, C. Burney and A. Mahlberg take up the quest, again, for an overhauled typology that will not only solve the diagnostic problem, but do justice to what they feel is evidence that points to the non-bipolarity of the functions. This evidence includes certain analyses of psychological type test data and the self-reporting of analysts who decided that their superior function was not opposite to their inferior.

"We propose, in this paper, to examine the hypothesized bi-polarity of the four functions, and suggest that perhaps the rigid dichotomizing inherent within the functional typology as so far conceived, has served as a kind of conceptual strait-jacket, inhibiting growth and development of the model." (p. 33)

In this reformulation they leave aside extraversion and introversion, and use both the primary and the inferior functions to characterize 12 types, for example, thinking primary - inferior feeling, thinking primary - inferior sensation, thinking primary - inferior intuition, etc. Though they are aware that introversion and extraversion must enter into this picture to create 24 types, they ignore the fact that it is difficult, if not impossible, to describe the functions as if they were neutral, existing without introversion or extraversion.

But there is an even more fundamental issue. The bi-polarity of typology was, in Jung's mind, a reflection of the bi-polarity of the whole psyche. Therefore, if we eliminate it we are on the road to eliminating it from the whole relationship between the conscious and the unconscious, and thus from Jung's psychology as a whole, and this would be a complicated and thankless task. If typology were clearly seen against the background of individuation, then the relationship between the inferior function and the superior has to be seen as the typological equivalent to the search for balance between the conscious and the unconscious.

The authors state: "the theory of the individuation process calls for this kind of balanced development of all the functions" (p. 34) and more explicitly, "The process of individuation consists, among other things, of bringing the least developed inferior function up to equal consciousness and strength with the other three, thus transforming the trinity into a quaternity." (p. 40) But this is not an understanding of the inferior function as Jung describes it and von Franz develops it. The inferior function does not lose its moorings in the unconscious and rise to the level of development of the other functions. If it did, individuation would be a broadening of the ego, but since the inferior function is rooted in the unconscious and maintains those roots despite the necessary task of developing it, it resists the ego usurping the functions, and makes it confront the unconscious as a partner in the quest for a new center, the self.

The authors have justly pointed to the diagnostic problem and the difficulty of developing statistical evidence, but when they say: "To what extent these 12 or 24-fold types actually occur in nature remains to be determined empirically" (p. 38) we can see that the word "empirical" has a very different meaning than it had in Jung. It is no longer the empirical facts of actual daily experience upon which he built his typology in the first place, but empirical taken in the sense of the evidence that mathematical analysis of test results might be able to produce. This is a very different kind of evidence than Jung would feel compelled to give, or Beebe when he says: "I have validated the bipolar assumption - that is, that thinking and feeling and sensation and intuition, are poles of a single axis - by studying psychological types in interactions, in dreams, and through inspection and empathy." ("Psychological Types in Transference... , p. 153)

We have returned to the problem of method in psychology and within Jungian psychology itself. Even Meier, that champion of typology, in making an impassioned plea for a more scientific approach to Jungian psychology, accentuates the statistical approach. He urges the universal use of the Gray-Wheelwright test, which he hopes will lead to the advancement of Jungian psychology in the academic world, and he says: "I would like to emphasize at this point that it is imperative that we support our own convictions by statistical evaluations as statistics are the closest we can come to the truth in psychology-11 ("Psychological Types and Individuation", p. 284)

If we understand this phrase that it is the closest we can come to the truth within the context of experimental psychology, and according to its norms and principles, there is no problem. But if we understand it more absolutely as the sole way psychology as a whole can proceed, then we are in an insoluble dilemma as far as Jung's psychology is concerned, for it would mean a virtual redoing of all Jung's work to "prove" it, as if it is unprovable in any other way, and we turn Jung into a dabbler who had many good intuitions but never proved anything, and we misunderstand the nature of the empirical evidence he is continually talking about. Finally, the most intriguing and interesting things of typology recede from sight because they are unknowable or as yet unknown by these statistical methods, as is illustrated by the general attitude of the experimental psychologists who consider Jung's four functions a fantasy.

Let's look at an attempt by Meier and Wozny to develop a better statistical basis to Jung's typology in their "An Empirical Study of Jungian Typology". They address themselves to the question: "What is the relationship between living Jungian types and those same types 'typed' by the Gray-Wheelwright test?" By Q-factor analysis they isolated specific groupings of analysts they felt would be equivalent to Jungian psychological types without assuming anything about what the Gray-Wheelwright scales actually measure.

"We correlated the response patterns, as recorded on each individual's score-sheet, with every other one for the 22 analysts, and then calculated which patterns were more similar to each other than to other patterns." (p. 227)

These types were compared with the self-typing of the analysts. They concluded:

"When we compared the 'self-knowledge' ratings with the types determined by the Gray-Wheelwright scores, we obtained little correspondence between them. Of the 22 analysts, 16 were found to have a conscious, typological appreciation of themselves that was different from (and, in some cases, opposite to) the way the Gray-Wheelwright types them" (p. 228) and this "...shed doubt on the advisability of using experiential judgments of Jungian analysts as possible criteria to evaluate the test's psychometric constructs." (p. 228)

In an attempt to overcome this problem they resorted to Q-factor analysis and found 8 distinct empirical subtypes which had no relationship with the self-typing and represented "8 distinct styles of responding to the test items." (p. 229) These empirical subtypes, they felt, could serve as the nuclei for the construction of a new test and concluded:

"... we would like to stress the importance of continued research on Jung's psychological types with methods that utilize objective, statistical designs. Only by using such procedures will we be able to separate fact from fiction and set Jungian typological test-constructs on firm empirical foundation." (p. 230)

Unfortunately, the use of sophisticated mathematical techniques does not create an unquestionable objective foundation that all will agree on. Extensive debates have and do rage among the factor analytic schools involved in the study of human differences. There is still the subjective factor of what data to collect and what technique to analyze it with. Meier and Wozny's study itself was soon challenged by N. Quenk in "On Empirical Studies of Jungian Typology". She underscored the difficulties in using Jungian analysts self-typing, and she found the use of Q-factor analysis inappropriate both because it used too small a sample and because this sort of factor analysis itself was not the proper choice to begin with. She compared it with R-factor analysis: "Unlike R-factor analysis, which operates on correlations between items or tests, Q-factor analysis operates on correlations between individuals over the range of a series of items or tests." (p. 221) Q-factor analysis generates types but

"...though the prototype is a discrete entity, no actual individual can be said to possess the characteristics of one type and one type only. A given individual is viewed as having more or less of the characteristics associated with the type in a quantitative fashion."

The theory of psychological types, however, assumes that the types are discrete entities which are qualitatively different, and that a given individual can be said to possess the "...characteristics of one type and one type only. Q-factor analysis therefore violates the assumptions of psychological type theory." (p. 221)

Quenk considers construct validation a much better way to proceed, a technique in which:

"... one must examine the theory of psychological types, generate empirically testable hypotheses consistent with the theory, test these hypotheses using appropriate research techniques, and finally examine how well the empirical results correspond with theoretical predictions." (p. 221)

Meier and Wozny's study had been preceded by other Q-sort examinations of Jungian typology. Mattoon summarizes the work of Cook (1971), Gorlow, Simonson, and Krauss (1966) and Hill (1970). Cook and Gorlow, Simonson, and Krauss developed items based on psychological types and had the subjects sort them according to whether they fit them or not, and then examined these groupings to see if they were more like Jungian types than what would have happened by chance. Hill administered various tests, including the MBTI, and in all the cases there was moderate support for Jung's formulation of typology. The use of R- and Q-factor analysis in relationship to Jungian typology can be traced at least as far back as W. Stephenson's 1939 article, "Methodological onsideration of Jung's Typology".

The question of bipolarity was taken up in a distinctive way by Loomis and Singer in their "Testing the Bipolar Assumption in Jung's Typology". They reorganized the questions of the Gray-Wheelwright and the MBTI so bipolarity would not be written into the structure of the test:

For example, an item such as:

At a party, I

(a) Like to talk.

(b) Like to listen.

was replaced by two scaled items separated in the test:

At a party I like to talk.

At a party I like to listen.

120 people were given the original Gray-Wheelwright and the rewritten version. "The results showed that 86, or 72 per cent, of the subjects changed their superior function from one questionnaire to the other. Further, in the GW revised version, 66 subjects, or 55 per cent, did not have an inferior function that has the hypothesized opposite of their superior function." (p. 354)

In a similar test of 79 people with two versions of the MBTI, 46% did not keep the same superior function, and 36% did not show the opposition between the superior function and the inferior. These results led the authors to abandon the assumption of bipolarity and the forced-choice format, and develop the Singer-Loomis Inventory.

In "A New Perspective for Jung's Typology" Loomis marshals factor analysis support for their inventory, for "without substantiation by a factor analysis, no inventory measuring typology will ever have the solid empirical foundation required for experimental research or for clinical applications." (p. 59)

Instead of 8 factors emerging, corresponding to the 8 psychological types, 5 appeared: feeling, intuition, thinking, introverted sensation and extraverted sensation, with no ready explanation of why this happens.

The lack of bipolarity in their test data leads them to reflections on Jung's structuring of typology.

"The authors questioned the conclusion implied through the constructions of the inventories now in use, namely that it is impossible for individuals to transcend the bipolar opposites under any conditions. It would appear that one of the most important aspects of Jung's psychology is being violated here, that of the eventual union, or transcendence, of opposites." (Interpretative Guide, p. 19)

While this language is not as extreme as that of Metzner, Burney and Mahlberg's, it still raises the same question when Singer and Loomis say:

"We believe that in the individuation process that does occur, that people do learn to come to terms with functions and attitudes other than their 'superior' ones, that even the so-called 'inferior' function can and does reach a very high degree of differentiation in some individuals." (Testing, p. 352)

The issue, really, is what "a very high degree" means. They base part of their case on creative people, and it is true that substantial development of the inferior function can take place, but the whole idea of its creative role is based on the fact not only of its differentiation, but a differentiation still rooted in the unconscious, and therefore, being able to draw on the unconscious' creative energies. Even in its creative role it retains, according to Jung and von Franz, its inferior character, an issue that we should examine further by looking at the inferior function in more detail.

The Inferior Function

The role of the inferior function is central to how Jung conceives his typology. It is embedded in the very structure of his Psychological Types where he balances every description of a particular type with one of its other side, which is embodied in the inferior function. And this is not just a didactic device. The inferior function is the doorway to the unconscious, the way we see from the point of view of consciousness that we must come to terms with the unconscious. The inferior function is not just a theoretical construct that Jung created in order to extend his ideas about the polarity of psychic energy into the realm of typology. Rather, it was the actual experience of the inferior function both in himself and in others that helped him formulate the more general theory of polarity. Jung's formulations about the inferior function are about one of the most critical and practical psychological problems that we all face.

J.L. Henderson suggests this when he says,

"...that a knowledge of the inferior function may contribute a most vital element to the formation of a psychology of the future by allowing psychotherapists to handle dynamically all those problems which do not properly speaking conform to the categories of the psychoneuroses or psychoses." ("The Inferior Function", p. 139)

The inferior function is not something that will be resolved like the challenges posed by the other functions. They are added to the ego and broaden and strengthen it; the inferior function will never be added in the same way. It is the stumbling block to complete ego aggrandizement. It prevents a total egocentricity for it makes it clear, often in a negative fashion, that the ego cannot control everything and therefore it presents the possibility of there being some dimension of the personality beyond the ego. If it presented this possibility as a theory it would join the large collection of things we "know" but don't truly understand and live. Instead, it involves us in our daily existence in an often painful and humiliating way in the recognition of our particular weakness.

Henderson continues:

"... analysis only provides a beginning for the self-knowledge required to trace the inferior function to its source in the whole process of life. It is only after analysis that the patient really comes to grips with it and has to work through the many stages of its integration into consciousness." (p. 139-40)

The inferior function is a constant opportunity for us to experience the dynamic nature of typology. In dealing with the inferior function we deal with individuation moment by moment. This is clearly expressed in Marie-Louise von Franz's The Inferior Function. This book, originally given as a series of lectures in 1961 at the C.G. Jung Institute in Zurich, has the flavor of experience. Here is someone who has actually come face to face with the inferior function again and again. And out of this concrete experience emerges a view of the inferior function which speaks powerfully to the issue of bipolarity. The fourth function can certainly be developed, but "when the fourth function comes up, however, the whole upper structure collapses. The more you pull up the fourth, the further the upper floor descends. A mistake some people make is that they think they can pull up the inferior function onto the level of the other conscious functions. I can only say: "Well, if you wish to do so, try. But you can try forever'.... (p. 17)

The conscious has to go down in order to raise the fourth, and she calls where they meet the middle realm, which is the place where transformation takes place. If consciousness loses its former place in which it saw itself as the center of everything, if we lose our ego-centricity, then the polarity of the psyche is overcome in a certain way. "The ego can take up a particular function and put it down like a tool in an awareness of its own reality outside the system of the four functions... Going to it (the inferior function) and staying with it, not just taking a quick bath in it, effects a tremendous change in the structure of the personality." (p. 59)

This new kind of consciousness must initially appear strange to us. We are so used to pursuing our goals by means of the functions which are dominated by the ego that this ego-less-ness might first appear as a loss of life or a vacuum. We don't experience our desires as we did before. We are not driven by the same search for gratification and we miss that drive. But we can actually be more capable and creative than before. It is simply that we are not in our acts the same way. Our ego has withdrawn and lives more in another center in this middle realm.

"There is a complete standstill in a kind of inner centre, and the functions do not act automatically any more. You can bring them out at will, as for instance an airplane can let down the wheels in order to land and then draw them in again when it has to fly. At this stage the problem of the functions is no longer relevant; the functions have become instruments of a consciousness which is no longer rooted in them or driven by them." (p. 63)

It is "hellishly difficult" (p. 66) to stay with the inferior function. But if we do, we get our "very appropriate, private discipline - invisible to the outer world, but very disagreeable." (p. 66)

After reviewing these attempts at restructuring psychological types, it is clear that questions of both diagnosis and method play a large part. The very complexity of behavior from which Jung's typology has been abstracted leads to diagnostic problems which, in turn, leads to attempts at overhauling typology to solve the problem. But what if the problem does not lie in Jung's typology, as much as in the difficulty of the empirical material itself, as Jung indicated many times? No doubt, Jung's typology will be expanded and refined, but if we are to do this properly we have to share in his appreciation of the tremendous welter of empirical material. If we grasp something of this complexity, then we are in a position to grasp something of Jung's formulations which relate directly to that material. We have to see the individual behind and through his psychological types, for that is how he wrote them, and since we cannot see his case material, his individuals, we must see our own, day by day, in our own lives. Failure to do this will make us think of reformulating Jung's types before we have fully fathomed what he is actually saying. J.L. Henderson compares the inexperienced typologist to a child who has a fine watch but can't really tell time yet. He tells of his own misguided attempts with his first patient that resulted in a misdiagnosis and in his feeling:

"And so I thought that if 1, who was a Jungian analyst with years of study and training behind me, could make such a glaring mistake, surely the type theory was unusable and must eventually be discarded as of any practical application in psychotherapy, to be kept only for its aesthetic enjoyment by a few superior minds." ("The Inferior Function", p. 135)

But he persisted, and not only used typology successfully, but developed some valuable principles concerning its use in general.

"Like all superior creations of the human mind it is more nearly perfect than its user, yet its only real function lies in its use. Such application requires a conscious awareness which is extremely hard to maintain until through practice it may become in a way habitual." (p. 134)

The use of the word "empirical" is highly ambivalent in relationship to Jung's typology, as we have mentioned before. It has become restricted to those results that could be supported by factor analysis, as if the actual contact we have with people and from which Jung derived his typology, is not empirical, that is, a direct experience of the concrete facts. Jung never limited the word "empirical" to statistical verification. Quite the contrary. He was convinced that certain things could simply not be handled this way, but this did not make them any less empirical. If extraversion and introversion can be statistically and experimentally demonstrated, it is because they are the most obvious and clear-cut of all the subjects that typology examines. But this does not mean that the four functions are illusions. They are refinements of introversion and extraversion, and as such, are more subtle and harder to measure. This is even more the case when it is a question of the relationship between the functions. If they cannot be measured by the standard statistical techniques, that is not because they do not exist, but rather, because the instruments we are using are not yet refined enough to see them. There is a value to refining these instruments and employing them in the field of typology where the dangers of projection are so great. But if we look at them as the only way we can know types, or know the individual, we will have succumbed to an equally great danger which is a misguided objectivism which concludes that since we cannot read braille with mittens on, the bumps don't exist. The world of experimental psychology and its sophisticated mathematics does not represent a panacea for the problems that Jungian psychology faces. A great deal of Jung's attraction today is precisely because he takes a broader view of things, and to make him over in standard categories would eliminate much of what he has to offer. It would be to succumb to an objectivism which represents only one half of the psychological method. Even the harder scientific approaches to human differences have their own difficulties. In 1982 G.L. Mangan, concluding his Biology of Human Conduct: East-West Models of Temperament and Personality, a 450 page review of Western and Russian literature, asks:

"What do we see in prospect for psychophysiology, and in particular, for differential psychophysiology? In both areas, there has been disappointingly little progress during the past decade." (p. 452)

It is not a question of ignoring developments in the experimental field or the use of sophisticated techniques in the analysis of type tests, but rather, of seeing that there is more than one way to arrive at genuine typological knowledge.

What can be done about the diagnostic problem? We cannot expect to be able to resolve it by reading Psychological Types or taking a short course any more than we would expect to become medical diagnosticians by reading the Merck Manual. We would not trust ourselves to a second-year medical student, but a typological diagnosis can be as demanding as a physical one. We expect the medical doctor to be trained not only theoretically, but on a practical level through his internship, and this actual training is carried out in analytical psychology through the training analysis, an innovation of Jung's that spread to psychoanalytic circles as well. But as we mentioned before, this is not equivalent to training in psychological types. Typology is an integral part of the process of individuation, but it is a distinctive view of it. What we need is training directly geared to typology, and there is no such training. This is why typology languishes much more than any need to reformulate Jung's work. The only training that takes place now is individual by individual, through the slow accumulation of insight that comes through personal experience, and this accumulation, since it takes place in relative isolation, is subject to distortion coming from the individual's personal equation and his projections and to the snail-like progress that comes from trial and error.

However, it is possible to envision an actual training program in typology. For example, it could build on the way psychiatric cases are often demonstrated, with actual interviews with the patient and subsequent discussions. In a good typological interview there are literally dozens and dozens of clues to diagnosis which range from posture to facial expression, gestures, verbal responses, off-hand remarks, reactions to physical situations, and so forth. And when the moment comes when the diagnosis begins to coalesce, there is a tremendous surge of perception as all these details become integrated around the axes provided by psychological types. These typological interviews could take different forms depending on the audience. Some might be geared to the demonstration of the dynamic process of typology that takes place within the analytic context. Others could show how typological knowledge can be arrived at by the individual and related to the situations he finds himself in during the daily course of events. Equally interesting would be a typological interview of a married couple, or a family in which the dynamics between the members slowly becomes conscious as their awareness of typological differences increases.

This sort of training could be integrated with the administration of type tests, the latest results from the experimental sciences, and so forth, but there is one major obstacle to its coming about. It demands that we admit how limited and defective our present typological knowledge is, and that we then devote our energies to remedying this lack. As long as we hold on to one particular method, subjective or objective, as long as we hold on to our distinctive point of view as the universal one which all other people should conform to, then we demonstrate the very situation that typology was meant to remedy.