A Short Orientation

On March 3

, 1719, what the Jesuit missionary Clemente Guillén was to call, "An Expedition to the Guaycura Nation in the Californias," left the Royal Presidio of Loreto for the unknown south, and the land of the Guaycuras. We are going to go on another and more cerebral expedition to the Guaycura nation to try to rediscover something of its history and geography in this largely forgotten part of Baja California Sur, Mexico, which stretches from present-day Ciudad Constitución south towards La Paz, and at whose heart were the missions of Nuestra Señora de Los Dolores and San Luis Gonzaga.At first glance such a project can hardly seem promising. One modern historian claimed that the mission of San Luis Gonzaga was the least mentioned of all the Jesuit missions in contemporary records

, or by the old historians of the Order,1 and described the country through which the Padre Guillén passed on a second expedition to La Paz as, "this broken and well-nigh impassable country, the worst in lower California."2Even in Jesuit mission times it had a reputation as being both a rugged and sterile place

, scarcely yielding its missionaries a crust of bread, and its Guaycura were seen as both primitive and intractable. Its missions were the first to disappear, and its history fell into oblivion. Even today traffic on the trans-peninsular highway speeds by to the west, but few strangers venture onto its dusty and rocky roads. The ancient heartland of the Guaycuras is all but forgotten.Yet all this should not lead us to imagine that it does not have a history worth recovering. It has, indeed, a rich history that has been appearing piecemeal during the 20th century as important documents have been published, and it is a history that even has some notable features. Modern American California, for example, owes the Guaycura nation a special debt, for the suppression of its missions and the exile of its people were due, in part, to free up resources to found the new California missions in the north. Further, its missionaries have left us a portrait of the lives of the Guaycuras that allows us to see something of how ancient Americans must have lived. Our task, then, is to recover this history and assemble it into a whole, to begin to ask about its wider significance, and if we are lucky, to occasionally catch a glimpse of the magic that has drawn travelers to Baja California for generations. The land of the Guaycuras is, in fact, a microcosm of human history from its hunter-gatherers onward, and it turns out to be a surprisingly well-documented one so we are afforded the double pleasure of discovering a small piece of history, and reflecting on what larger lessons it has to teach us.

Video

The video

, An Expedition to the Guaycura Nation in the Californias, is a visual companion to this book, providing vivid glimpses of the caves, missions and ranchos of the Guaycura nation. See back matter.Acknowledgments

A mission era history of the Guaycura nation would not have been possible without the work of people like Ernest Burrus, Miguel León-Portilla, and W. Michael Mathes who published many of the documents that we will make use of here. The story of the missions of Los Dolores and San Luis Gonzaga naturally plays out against the panorama of Baja California Jesuit history as a whole, and our task in this regard has been made much easier by Harry Crosby’s finely crafted Antigua California, and his Last of the Californios in regard to the time of the ranchos, a book which nurtured my fascination for Baja California long ago. Many librarians and curators helped me collect the materials that have gone into this book, and I owe particular thanks to the Interlibrary Loan service of the Klamath County Library, especially Inca Sefiane.

Hilda Silva Bustamente and her staff made us welcome at the Pablo Martínez Archive in La Paz, and she helped us obtain copies of important documents. Harumi Fujita and Quintín Muñoz Garayzar of the Anthropological Museum in La Paz encouraged our interest in the archaeology of Baja California, and Quintín traveled with us on our first visit to the rock shelters of the Guaycura nation, and he and his family have always made us feel at home.

Paul and Francisca Jackson have made our travels through Baja California Norte more pleasant, and the Madres Adoratrices of La Paz have always taken us in with warm smiles. Monseñor Juan Giordani who spent many years on the rocky roads of the Guaycura nation in his old pick-up truck building chapels in all its corners, right up until his death in January, 2001 at age 94, made us welcome in Las Pocitas, as Hermana Mercedes Hurtado Moreno does to this day.

And we owe special thanks to the people who live in the Guaycura nation today who over the years as we have traveled there have greeted us with the traditional hospitality of the sierras of Baja California.

A Note to the First Edition:

We produced an experimental edition in November, 2002,

and then an updated and reformatted first edition in October, 2003. For the most part, the

changes in the text had to do with adding more material to Chapter 10, Archaeology in the

Guaycura Nation.

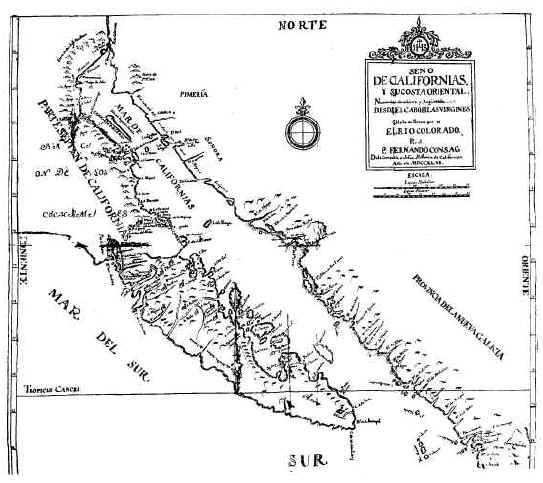

Map 1. Fernando Consag, 1746

Chapter 1

First Encounters

As far as we know, there never was a Guaycura nation, but rather, bands of hunter-gatherers, or rancherías, bound by linguistic and cultural bonds, and not above warfare among themselves. For Clemente Guillén, the Guaycura nation was these uncontacted bands who lived south of Loreto where the present highway leaves the Gulf coast and climbs into the Sierra de la Giganta, and north of La Paz, for this was to be his own mission territory.

When Clemente Guillén set out from Loreto, the first mission and capital of California, in March, 1719, the heartland of the Guaycura nation had never been explored, but this is not to say its inhabitants had no knowledge of Europeans. In the early 16th century their land had seen the sporadic activities of explorers, pearlers, and the occasional pirate. Loreto had been founded in 1697, and word of it must have passed from Indian ranchería to ranchería.

The Spanish had been exploiting the oyster beds of the Gulf from their first voyages of exploration in the first half of the 16th century, which had included those off the Isla de San José and its smaller neighbor San Francisco just off the coast of Apaté where the mission of Los Dolores was to be founded, and the pearlers knew of its spring. Explorers had anchored in the bay of La Paz, or at the Cape, or along the West coast. The expedition of Sebastián Vizcaíno, for example, had sailed to the Bahía de Santa María Magdalena on the Pacific coast of the land of the Guyacuras, and had reported on fish traps made of poles that stretched for a mile there, and of a great number of Indians who had with them an incense made from the resin of the ciruelo tree.

Vizcaíno describes his 1602 expedition’s encounter with the Indians of the Bahía de Santa María Magdalena: "There came out to the said ensign a large number of Indians from different places with their bows and arrows and fire-hardened darts, although in peace, they gave up their arms as a sign. They are well-formed people of good physique, although naked and living in rancherías; their ordinary food is fish and aloe root because there is a large quantity of them of many kinds, and they fish with weirs, and also have many clams and mussel."1 The Vizcaíno expedition also anchored in the nearby cove of Santa Marina, "where Indians like the others came out to them, and as a sign of peace they gave them their arms, which are arrows and little darts of branches which they also use to fish."2

If nothing else, the Guaycuras of the interior must have heard of the massacre of the bay of La Paz Indians by Admiral Isidro de Atondo y Antillón on his ill-fated expedition of colonization to Baja California in 1681. As Padre Clemente described it: "As a result of this entry, some of the natives became more obstinate, rebellious, and averse to the Spaniards, because of the cruel action of the admiral, who as he withdrew and left a quantity of maize on shore, boarded his ships. As the Indians hastened to scoop up the grain, he fired a closely packed charge of small shot causing a large number of deaths among the natives. The massacre resulted in a horror of the Spaniards inherited from fathers to sons." The natives there, he goes on, are "completely unchecked, are most ferocious and angered because of Atondo’s cruelty."3

The whole of the peninsula south of Loreto was going to prove to be difficult for the Spaniards to gain a foothold in, and just as difficult for them to keep. In July, 1704, for example, when the Jesuit missionaries Juan María Salvatierra and Pedro de Ugarte, accompanied by the Spanish soldier Francisco Javier Valenzuela and two Indian interpreters, reconnoitered the Gulf coast south of Loreto, they were ambushed by the Monquí, part of the greater Guaycura family, and only a heroic one-man charge by Valenzuela, which so surprised and terrified the Indians that they prostrated themselves on the ground, saved the day.

The mission of San Juan Malibat had been founded among the Monquí at Liguí in 1705 by Padre Juan de Ugarte, and had always been rather ill-fated, and its history was not going to change. Ugarte had enthusiastically enticed the Indian children to dance and sing as they trod the adobe mud in order to make bricks for the church, and he had successfully confronted the local demon of the mountains Monquimon, but he had founded the mission in a location that lacked adequate water.4

Another entrada along the Gulf coast in 1706 by Jaime Bravo, Capitán Esteban Rodríguez Lorenzo and seven soldiers, along with some Indians, ended in disaster. Some of the soldiers came upon a fire where the Guaycuras had been grilling fish, and had left behind some fish livers. Despite the warnings of the Indians that these livers from the botete fish were extremely poisonous, they proceeded to sample them in various degrees. Two of them died.5

Clemente Guillén

Clemente Guillén de Castro (1677-1748) was born in Zacatecas, Mexico, and joined the Jesuits at Tepotxotlán in 1696.6 Miguel de Venegas in his life of Juan María Salvatierra, the founding missionary of California, tells us that Salvatierra, when he met Guillén and Juan de Guenduláin as novices, prophesied: "You will both go to California, but one will remain and one will return." Guillén, after teaching grammar and reading philosophy in Oaxaca, was to request the California missions, and die there. And Guenduláin as a Jesuit visitador general, charged with inspecting the missions of the northwest province of New Spain, toured California and returned.7

But prophecy or no, Guillén’s arrival in California was anything but propitious. He set out in 1713 with two fellow missionaries, Benito Ghisi and Jacobo Doye, but the boat they sailed on was so poorly constructed that its sailors feared to embark on it, and their fear was confirmed when it broke apart in a storm. Ghisi was caught below deck and drowned, and Guillén and Doye with some of the crew clung to the stern and were washed back up on the mainland.8 This tragedy illustrates a constant theme in Jesuit mission history. They were dependent throughout their stay in California on supplies, including wheat and corn, from the mainland, and yet they often had inadequate transportation for those vital necessities. And the loss of this boat was to also delay the much desired opening of the South.9 Padre Clemente finally arrived in Loreto in 1714, and soon after was assigned to the mission of Liguí, some 20 miles to the south.

By the time Guillén arrived, it was without a resident missionary, and he, himself, was to remain there intermittently from 1714 to 1721. During this time the mission was subjected to a series of damaging raids by the Pericú from the Isla de San José who plundered the church, and who, in turn, were punished by a Spanish expedition from Loreto. The mission also suffered from a lack of alms, for its benefactor had gone bankrupt, as well as from a scarcity of fresh water. And most of all its neophytes had been reduced to a small number by repeated epidemics, and therefore could easily be taken care of by the neighboring mission of Loreto. Therefore it was decided to abandon the mission and found a new one.

In 1716, Salvatierra, along with Capitán Rodríguez and soldiers and Indian converts from Loreto, went to La Paz by ship hoping to open the south to missionary activity, and to find a port for the Manila galleons. With them were three Guaycura who had been captured before in the La Paz area, who they were going to liberate in order to show their good intentions. But the Loreto Indians ranged ahead of the Spaniards and encountered some Guaycuras, and as the Guaycuras fled, they trapped some of the women and killed them, effectively ending this attempt to open up the South.

But on the whole European activity was on the fringes of the Guaycura nation, and thus Guillén’s first journeys had both the fascination and danger of first encounters for both sides. For the first time the Indians were to come face to face with the Spaniards and their weapons and clothes, their horses and mules, and their very desirable food and gifts. The Spaniards, for their part, had two goals. One was to expedite the discovery of a port for the supply of the Manila galleons who, after their long Pacific voyage, were in dire need of fresh water and food. The other was to prepare for the evangelization of the Guaycura nation.

Physical Geography

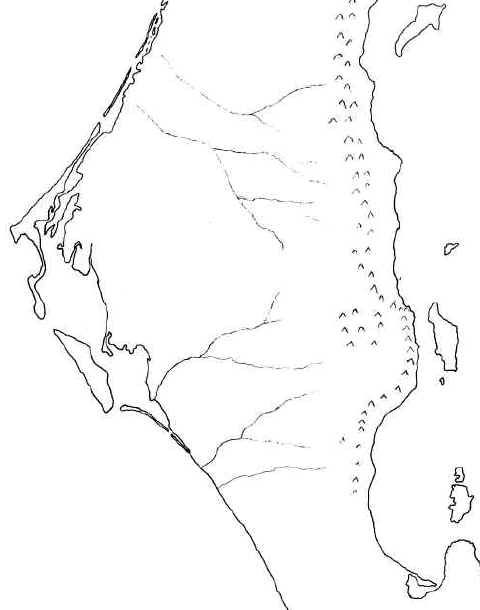

The land of the Guaycuras that the Guillén party was about to enter consisted of mountains to the east which often extended to the Gulf, and plains to the west. (Map 2) Water, while never abundant, was to be found more often in the east, while the western plains were much drier. The land was cut by a series of dry river beds, or arroyos, which sometimes contained springs, and on occasion filled with the roaring waters of flash floods. But periodic droughts could last for years. In terms of rainfall, it was a desert, but this desert of rock and thorns was filled in places with brush and small trees, as well as desert plants, and occasionally there was a small oasis.

Map 2: The Physical Geography of the Guaycura nation

The Expeditions of Clemente Guillén

Fortunately, Padre Guillén left us detailed descriptions of his two expeditions. Peter Dunne, a modern Jesuit historian, called these trip journals of 1719 and 1720 "long and prolix."10 But that was only because he read them as a stranger would read a long list of place names in a country he had no personal experience of, rather like us reading a phone book. In actual fact, they are the practical notes of an explorer who is opening up a new land for those who will come after him. Read in this way they are a gold mine of information not only for their occasional ethnological insights, but because they help us reconstruct a geography of the Guaycura nation, and glimpse this country at the moment that it was first revealed to European eyes. On both journeys, the Spaniards and their Indian companions from the missions to the north made use of local guides whenever possible, and followed the Indian foot paths from ranchería, or Indian gathering place, to ranchería, sometimes struggling to improve them to allow the passage of their horses and mules.

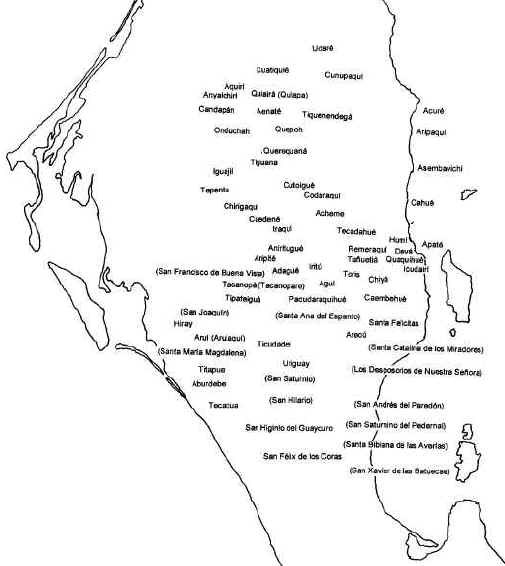

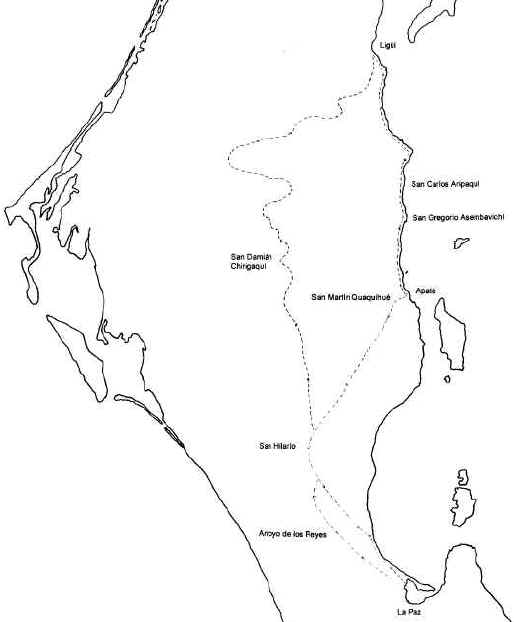

A Guaycura Geography

If we put the geographical information found in Guillén’s expeditions, together with other early missionary accounts as well as surviving place names, we arrive at a Guaycura geography. (Map 3) The names in parentheses are rancherías for which only the Spanish names have come down to us. This map is, no doubt, skewed because we know the names of places where the missionaries traveled and recorded their journeys. This leaves the Pacific coast rather empty. Yet Guaycura territory on the west coast stretched down towards La Paz in the south and north along the west coast past San Javier. The rancherías are best thought of as the hunter-gatherer bands, themselves, and their favorite haunts which had water, at least in certain seasons.

Map 3. A Guaycura Geography

The 1719 Expedition

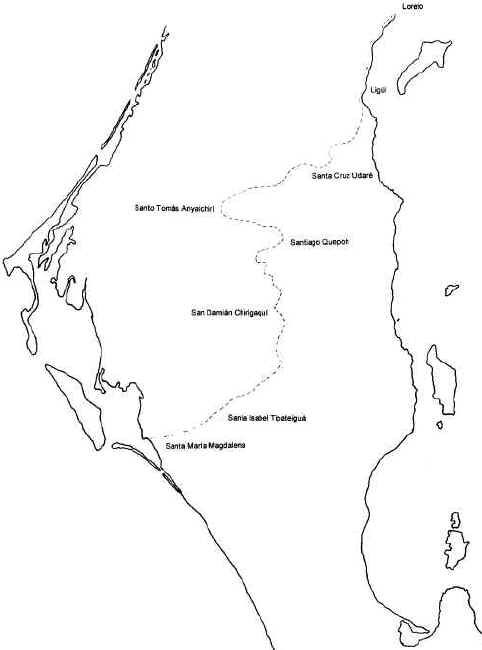

"An Expedition to the Guaycura Nation in the Californias," begins Padre Clemente’s journal of 1719, "and the discovery by land of the great Bay of Santa María Magdalena on the Pacific Ocean. Under the command of Captain Don Esteban Rodríguez Lorenzo, the first conqueror of California, with a squad of twelve Spanish soldiers from the Royal Presidio of Nuestra Señora de Loreto and another of fifteen friendly Indians and two interpreters. Beginning on the 3rd of March of this year, 1719."11 (Map 4)

Map 4. The 1719 Expedition

March 3, 1719. Captain Rodríguez leaves Loreto and goes to the ranchería of Nautrig, or Notri where the horses and mules are. He travels four leagues that day, which is roughly 20 kilometers, or 10 miles, but the length of a league in Guillen’s hands was probably quite flexible and influenced by the difficulty of the terrain.12

March 4. The expedition goes up Chuenque Grade which falls precipitously into the sea, and after 5 leagues reaches Liguí where they pick up Padre Clemente at his mission of San Juan Malibat.

March 5. "We left San Juan Malibat …"13 They advance another 5 leagues climbing the Sierra de Santa Ursula and stop near the promontorio de San Nicolás. Both names appear unknown today, but the route seems to follow that of the present highway where it climbs into the sierra south of Juncalito.

March 6. 5 more leagues to Udaré which they baptize Santa Cruz Udaré and where they find some Guayacurans from Cunupaqui, home of one of the interpreters. The rancho of Santa Cruz is still active, and the name Cunupaqui (Cunopaqui) lives on as the name of an arroyo to the southeast. The Cunupaqui are invited to bring their children to be baptized at Cuatiquié.

March 7. 7 leagues following the arroyo of Santa Cruz brings them to Cuatiquié where they rendezvous with the Cunupaqui, baptize the children, and stay over.

March 9. 6 more leagues bring them to Anyaichirí (the present-day ranch of Andachire). That night a local Indian leader gives them a fervid oration about the dangers they face from the Indians in the south, all the while moving his bow and arrows in time to his words.

March 10. 5 leagues to Quiairá in the vicinity of Jesús María.

March 11. 4 leagues to Quepoh in the area of the present-day ranch of San

Miguel Quepoh. The Spaniards please the Indians by singing hymns.

March 12. 4 leagues to Querequaná (probably in the area of Los Cerritos) led by guides regaled with tobacco, knives, blankets and sack cloth.

March 13. 3 leagues to Tiguana.14

March 14. 3 leagues to Cutoiqué near Tepentu.

March 15. 6 leagues to Codaraqui which may be near modern Codey. The natives give them a visor, or crown, as a symbol of friendship.

March 16. 5 leagues to Chirigaqui which is the present-day mission of San Luis Gonzaga. The natives act suspiciously in the eyes of the Spaniards who are fearful of ambushes, but nothing happens. Here the soldiers are described as "cutting branches," that is, getting forage for the animals from mesquite or dipúa trees, and the Indians are living in huts (ranchos), which most likely meant flimsy low brush shelters, rather than more permanent homes.

March 17. They rest here.

March 18. Once again the Spaniards are suspicious because the guides who promised to take them to the south to Aniritugué, (Iritú?) which is to the south, guide them up a wash to the east for 2 leagues where they encounter a large number of Indians in the arroyo, with the women safely out of the way seated on a high bank. The expedition parades by them in good order. In this way they arrive at Cuedené, probably modern day Cuedán. There are 7 rancherías in the area. Guillén tells us the expedition has a "carriage," which W. Michael Mathes, the translator of this text into English calls, "an ammunition carriage, similar to a caisson."15 This carriage probably made the trip more difficult, because the explorers were already using a great deal of energy to improve the Indian foot paths for their animals, and there is no evidence that it was used on the expedition to La Paz the following year.

March 19. West 5 leagues past 5 arroyos to Adagué, probably in the area of rancho San Andrés. They explore to the southwest down the arroyo, and climb a hill from which they see the mountains on Isla Margarita in the Bahía de Santa María Magdalena.

March 20. Arrive at San Joaquín (no Indian name given) one and a half leagues away, and see fenced areas that the Indians used in hunting rabbits.

March 21. 5 leagues to Santa Ana del Espanto passing rancherías. In one of them they see blood-stained and broken bows and signs of a human body being dragged. This is an indication of the warfare carried on by neighboring rancherías. During the night watch Ignacio de Acevedo claims to have seen a ghost in a tree.

March 22. Following the bed of the arroyo for 5 leagues they arrive at a little island in it, Santa Isabel Tipateiguá. An advance party has been exploring ahead of them and reporting back for the past few days in order to determine the best route to the bay. This party now comes upon Indians at San Benito Aruí, so busy hunting rats that they don’t hear the Spaniards until they are on top of them. In surprise, they blow their whistles to alert their companions and threaten to fight.16 The explorers calm them and give them hardtack and little gifts, and receive feathers and deer skins in return.

March 23. The whole party travels 5 and a half leagues to San Benito Aruí. The advance party reaches an estuary surrounded by thick mangroves.

March 24. Captain Rodríguez tries to find a route to the Bay of Santa María Magdalena. The Taconoparé come to camp and the explorers give them some striking feathers in order to encourage them to show them the way to a water hole on the bay.

March 25. There is a spring at Aruí, but the Spaniards go back to Tipateiguá where there is pasture for the animals.

March 26. Cabo, or Corporal Francisco Cortés de Monroy sets out to find a route to the bay and travels 17 leagues. Near some dry lakes they find some abandoned huts (ranchos) and fences (casillas) of cardon.

March 27. Monroy goes on and after 3 leagues arrives at the sea opposite Isla Margarita at one of the channels into the bay, and they see whales going in and out. Exploring the shores of the bay, they find an Indian trying to burn mangroves who guides them to the ranchería of Santa María Magdalena. There is a well there, and the explorers try to water their animals by scooping the water out with the Indians’ containers made of roots and rushes. The Indians give Francisco de Rojas a mother-of-pearl shell, but say that it came from the Gulf. Monroy leads the expedition back towards Aruí.

March 28. Monroy arrives at Aruí, then goes on to Tipateiguá.

March 29. More explorations down the wash of Aruí.

March 30. Due to the exhaustion of the animals, the Captain decides not to explore further south towards Cabo San Lucas. They leave Tipateiguá and go 6 leagues to Santa María Tacanoparé.

March 31. The explorers take a more direct route and reach Quedené after 7 leagues.

April 1. They arrive at San Francisco de Buena Vista between Chirigaqui and Codaraqui on the Quedené arroyo. 6 leagues.

April 2. 7 leagues. Arrive at Cutoigué.

April 3. 3 leagues to San Andrés Tiguana and explore the area of the arroyo.

April 4. 3 leagues to Querequaná. Explore upstream.

April 5. More explorations of the Querequaná area.

April 6. 4 leagues to Santiago Quepoh. Explore 3 leagues to Tiqenendegá.

April 7. 1 league to Aenatá. Explore the area. The infants of Quiapá are baptized.

April 8. 6 leagues through heavy brush to Aquirí, stopping at Candapán, territory of the Indians of Anyaichirí. This is the same arroyo as Udaré, which is at the end of the Guaycura territory, "although on the opposite coast they extend further to the northeast."17

April 9. Arrive at Cajalchimín.

April 10. On to Omobichimincajal in the arroyo of San Javier.

April 11. On to Cajalloguoc in the same arroyo.

April 12. Arrive at San Pablo where Juan de Ugarte welcomes them.

April 13. Pass through San Javier.

April 14. They descend the sierra to Loreto where they are greeted with joy.

While the trip to the Bay was a failure in terms of finding a harbor for the Manila galleons because of the lack of water, and thus the inability for a mission to be established there, the second objective had been achieved. Contact had been made with many rancherías in the Guaycura nation. The Guaycura country was now open for the establishment of a mission. Soon an ambitious plan was set in motion to open up the South. It called for the creation of not one mission, but two. Juan de Ugarte had just built El Triunfo de la Cruz, the first boat constructed in Baja California by laboriously hauling timbers from the Sierra de Guadalupe. Its first task would be to take Padre Jaime Bravo and Ugarte to the Bay of La Paz to establish a mission there while Clemente Guillén would lead an overland expedition to La Paz and choose an intermediate mission site along the way. Then La Paz would be joined to Loreto not only by the sea, whose storms often made travel precarious, but by land, as well.

The 1720 Expedition

"Expedition by Land from the Mission of San Juan Malibat to the Bay of La Paz on the Gulf of California, 1720."18 It consists of 3 soldiers, 4 servants, and 13 Indians from San Juan Malibat and Loreto.19 (Map 5) The actual manuscript of this diary, in contrast to the one of 1719, has enough corrections and signs of heavy usage to make us wonder if we don’t have before us the original pages that Guillén wrote on this rugged journey. The title of the manuscript has crossed out en Californias and so matches the en Californias of the 1719 diary. Guillén gives as one of the soldier’s names Ignacio de Rojas, but he inadvertently starts writing Ignacio, and then Acq_a_, which might be a clue to the name of one of the other soldiers on this journey. 20

Map 5. The 1720 Expedition

Monday, Nov. 11. The expedition leaves Liguí and travels 6 leagues to Catechiguajá.

Nov. 12. They arrive at Pucá

, the end of Laimón territory.Nov. 13. The sea is rough

, so instead of sending their supplies to Apaté, they make the fateful decision to transport everything overland by mule. In contrast to the El Triunfo de la Cruz which sailed to La Paz with a stop at the Isla de San José in 3 days, Guillén’s expedition was going to take a total of 26.Nov. 14. 7 leagues to Acurí where the Guaycura

, or Cuvé, nation begins.Nov. 15. 5 leagues to San Carlos Aripaquí over 2 difficult summits.

Nov. 16. To Asembavichí. (Timbabichi) 3 leagues. The explorers see saline deposits and grinding stones.

Nov. 17. 7 leagues to Cohué = Cogué. 2 more leagues exploring to Acui, a small water hole.

Nov. 18. Arrive at Apaté after 4 leagues. Thus far the expedition has been traveling along the coast. At Apaté Guillén finds that salt water has seeped into the wells

, but about a league up the arroyo there is running water from two springs in a limestone mountain, and from water coming from higher up in the arroyo. There are also two patches of land along the arroyo that give the promise of irrigating crops. This is to be the site of the new mission of Nuestra Señora de Los Dolores. Padre Clemente writes: "All of this is the best area we have found."21Nov. 19. But now the most difficult part of the journey begins. The way along the coast is blocked because the sierra falls into the sea. They are forced inland up into the Sierra del Tesoro. An advance party reaches Devá whose natives blow whistles in alarm

, but the Aripaquí who are serving as guides calm them.Nov. 20. The whole party goes up the 3 leagues to Devá

, a place with grass and marshy spots.Nov. 21. 3 leagues of difficult trail to avoid marshes in order to reach Quaquihué. (Kakíwi) They explore 2 leagues further toward Ichudairí. The route from here on is much harder to connect with modern place names.

Nov. 22. The explorers arrive at Caembehué after 6 leagues of difficult trail.

Nov. 23. Half league down a very rocky wash to Santa Felicitas. The Spaniards want to return to the coast in order to be sure they will find La Paz. An advance party goes out

, but the guides take them by error 6 leagues to the northeast. From the top of a mountain they see San Evaristo on the Gulf.Nov. 24. 5 leagues to Arecú. Then a party explores again toward the coast but cannot go through the mountains

, and so they must head south.Nov. 25. 3 leagues to Santa Catalina de los Miradores. The explorers try again to find a way to the coast with no success.

Nov. 26. 2 leagues to Los Desposorios de Nuestra Señora. Another attempt to reach the Gulf.

Nov. 27. They stay in camp to explore the mountains that prevent them from reaching the coast. They sight the Bay of La Paz and its palm groves 12 leagues away. The rough terrain is taking its toll. Juan Antonio de Covarrubias collapses

, probably from heat exhaustion. The advance party is out all night and limps in the next day.Nov. 28. A rest day. A council is held about whether it is better to go back because supplies are getting low

, or to push on to La Paz. They decide to go on despite the fact they will soon be reduced to eating agave and yucca, and even their horses.Nov. 29. More explorations to find a way through the mountains.

Nov. 30. 5 leagues to San Andrés del Paredón. Some of the Indian guides slip away for fear of enemy rancherías and hunger.

Dec. 1. One and a half leagues along an arroyo to San Saturnino del Pedernal.

Dec. 2. Santa Bibiana de los Averías. 6 leagues. They found in

"a small declivity a great many flints finer than any thus far found in this land."22Dec. 3. 4 leagues to the northeast.

Dec. 4. 4 leagues to the north and then 2 leagues to the east and down a steep slope through the brush

, and finally after 2 more leagues they reach the sea. They determine that La Paz is still off to the south. They arrive at San Xavier de las Batuecas.Dec. 5. A half a league along the beach until a cliff forces them inland. They go 6 leagues

, keeping to the beach when possible.Dec. 6. 10 leagues. There are more cliffs

, but between 3 and 4 in the afternoon they arrive at the estuary that separates them from La Paz and see that El Triunfo de la Cruz is still in port. Canoes transport them to the new mission site where they are greeted by Jaime Bravo. The men recover and are soon helping to build the mission. During the construction, a bell (cascabel) of "ancient manufacture" is dug up. Perhaps this was a small bell used as trade goods by previous explorers. 23Members of the Guillén party explore to the southeast and encounter a group of Indians who flee on their approach

, leaving them wondering whether they were Guaycuras or Cubíes. The place where they came upon these Indians Guillén tells us was not a ranchería "because the natives did not have water, and they were only searching for food."24 They go on another expedition to the west and northwest. They are not going to try to repeat the last part of their route to La Paz. Juan de Ugarte has sailed to Loreto and brought back supplies, and now he will return with some of the expedition’s worn out Indian allies who are going back to the mission at Liguí. 251721

Jan. 10. They leave for Liguí and go 3 leagues. Their supplies are transported across the bay to spare the mules.

Jan. 11. They go up the arroyo de los Reyes 6 leagues.

Jan. 12. They continue along the arroyo

, and after 4 leagues they realize they had seen part of this trail on their way south. They go 2 leagues further up into the mountains and come to a waterfall.Jan. 13. They leave the arroyo de los Reyes and arrive at San Felix de las Coras. The people flee

, leaving 3 children behind. At sunset men and women return to the ranchería. The women hide themselves, but one old lady comes down while the men are still up on the heights, shouting in Cora "which our friends the Cubíes do not understand."26Jan. 14. 8 leagues finds them at San Higinio del Guaycuro which they characterize as a ranchería of Guaycuras

, or Cubíes. They continue and encounter their old trail once again, having arrived at the arroyo of Santa Bibiana de las Averías below where they had passed going south. They call this new stopping place San Hilario.Jan. 15. They explore down this arroyo and find a good supply of running water and land for planting. They return to San Hilario and follow their old trail 5 leagues to San Saturnino.

Jan. 16. They follow the old trail one and a half leagues and meet some Indians who guide them to Pacudaraquihué. They give the natives sandals

, tobacco, knives and feathers, and receive, in turn, feathers, ribbons, braiding the Indians use in their hair, and flints. Then the Spanish make a mistake. One of the Indians tells them that he cannot come into the ranchería because his father-in-law was there. This was probably some sort of taboo. The Spanish laugh and the Indians are later hostile to them.The explorers are looking for a better route and ask the natives to lead them to Chiyá. Perhaps the Spanish had heard of this place which was to become the second site of the mission of Los Dolores when they were passing through the area around Apaté.

Jan. 17. Thirty Indians from Pacudaraquihué accompany them to Remeraquí

, and when they near it they string their bows and run to the ranchería. Tension is in the air. One of the Spaniards spurs his horse and jumps over a large clump of brush to impress the Indians. The Spanish present the Indians with feathers which are a sign of friendship. The Indians respond with ribbons, feathers, braided cord, and lances with flint tips.Jan. 18. The Indians come to the camp and ask the natives who are with the Spaniards to run

, for it is the custom for those receiving a visit to go out and meet the visitors, and then for all of them to run to the ranchería. The Spaniards, however, are suspicious of the invitation. Tension builds. Indians follow the Spaniards instead of going ahead of them. One jabs the Corporal’s horse. Another jabs the horse of another soldier. One of the Indians with the Spaniards is asked where the Spaniards’ bows are and whether they are women, and whether the Spaniards are afraid, and if afraid, why did they come? In this way the explorers reach Aripité. The Spaniards want to go on to Cuedené, and after some hesitation, 30 Indians go with them, but the Spaniards worry that others have remained behind to plot an attack. On leaving Aripité they see a pitahaya cactus broken into pieces and some of the larger parts of it pinned to the ground with sharpened sticks. This is understood as a declaration of war. They go on to Anirituhué, leaving many of the Indians from the previous ranchería behind. They exchange gifts and receive arrows and little flint-tipped lances. They go on to Cuedené and then to Chirigaguí, passing 2 rancherías along the way for a total of 12 leagues.Jan. 19. They leave early and pass near Codaraguí

, then pass Cutoihuí and Tiguaná without finding people because in this season they are in the mountains collecting agaves. They arrive at Guerequaná for a total of 12 leagues.Jan. 20. 4 leagues to Aenatá

, passing Quepoh and Fiquenendegá.Jan. 21. 5 leagues to Quatiquié

, passing Onduchah, a branch of the Anyaichiri people and Candapan.Jan. 22. 6 leagues. Arrive at Udaré where 3 of the Indians who have accompanied them are from. The head man of the Anyaichirí is there

, and the three report the hostility of the Pemeraquí and Aripité. In the most silent part of the night the head man makes an oration against these Indians. This was, perhaps, the same head man who had given an oration at the beginning of the 1719 expedition. (March 9, 1719)Jan. 23. After 8 or 9 leagues they arrive at Liguí.

Guillén

’s trip journals contain a wealth of topographical detail, only hinted at this summary, and it would probably be possible to reconstruct the routes of these expeditions in detail, and attempt to follow them out on the ground. Such a modern expedition to the Guaycura nation would not only be an exciting adventure, but could possibly provide a rich harvest of information about the Indian rancherías and the early ranchos that followed them.These first encounters generated strong and conflicting emotions on both sides ranging from fear to exhilaration

, and what was set in motion was the collision of two cultural universes, not only in the material sense, but much more profoundly in an inner psychological sense. This collision will now start to play itself out against the stark background of infectious diseases that might have been introduced into the Guaycura nation by these very expeditions.